Catholics in the U.S. are familiar with all kinds of “second collections” taken up in their parish churches. But only one can claim status as the first ever!

Recognizing a need to call the faithful to support missionary work among African American and Native American Catholics, the U.S. Catholic bishops established this Catholic Church charity for the Catholic Missions in 1884 to administer a national collection—the first of its kind in the United States—to support missionary work.

Ever since the first Collection in 1884, the Commission has administered the yearly, national Black and Indian Mission Collection. The generosity of the good People of God allows the Commission to give helpful grants to dioceses across the country to operate schools, parishes, and other missionary services that build the Body of Christ in Native American, Alaska Native, and Black Catholic communities.

History

A Voice for Catholic Indians:

The Birth of The Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions

One in a series of historical reflections by Tim Lanigan

At a moment when the vice president of the United States, the speaker of the House of Representatives, and six of the nine justices of the Supreme Court are Catholic, it may be hard to imagine a time when Catholics were not only a small percentage of the population, but a marginalized one as well. For example, in the 1850s, only five percent of Americans were Catholic. Today, it’s 25 percent. But more importantly, in the late 19th Century, Catholics had little representation in the seats of power.

It was just this lack of an effective voice in the nation’s capital that led to the creation of one of the oldest, most long-lasting Catholic institutions in the United States. This year marks the 140th anniversary of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions. It was created during a moment of what Philip Weeks, a scholar of American Indian history, has called a period of “intense anti-Catholic sentiment” in the nation.

Hundreds of Catholic missionaries had been sharing their lives and religion with American Indians since Franciscan friars arrived in New Mexico in 1540. By 1630, 25 mission residences served some 35,000 Christian Indians in New Mexico’s 90 churches. Among the better known missionaries in North America was St. Isaac Jogues, who ministered to Indians in 17th Century New France. Another well-known missionary was Fr. Peter DeSmet, who spent 50 years among Native Americans in the mid-West and West. It was a French priest, Fr. Jacques de Lamberville, who in 1675, studied the catechism with an 18-year old Mohawk woman and helped lead her along the road to becoming one of America’s most famous saints – Saint Kateri Tekakwitha.

The collision of two cultures, one of the European immigrants, the other of Native Americans, didn’t go smoothly. Almost 400 years after Columbus landed in Hispaniola, and more than 250 years after the English landed in Virginia, settlers in the United States and Native Americans were still struggling with each other over many issues, especially over land. Despite many treaties with Indian tribes, American settlers seized Indian lands, first crossing over the Appalachians and then moving across the Mississippi River. Treaties were signed, then disregarded. By one estimate, Americans broke 370 treaties on their way West.

American missionaries, many of them Catholic, shared their lives and religion with tribes throughout the United States. While the popular culture of Americans fed on wild tales of Indian savagery, those who knew them best, the missionaries, came to respect their cultures and common decency. Fr. DeSmet, for example, once cited a New Mexico court decision that declared that “vastly less” crime would be found among a thousand of the worst of the Pueblo Indians than among an equal number “of the best Mexican or Americans in New Mexico.” He went on to note that every Pueblo village had erected a Catholic church, each with its own priest, and that the Pueblos were a “peaceable, industrious, intelligent, honest and virtuous people.”

It was this close relationship with Native Americans that called into question a decision by the federal government in 1870 to test a new government policy in its dealings with Indian tribes. In 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant was fed up with the corruption and public scandals within the government agencies handling Indian affairs. In what became known as “Grant’s Peace Policy,” Grant decided to hand over jurisdiction of the tribal lands to Christian missionaries, people who knew the Indians well and were more likely to put the interests of the Native Americans above their own interests.

What stunned Catholic missionaries was the way the jurisdictions were handed out. President Grant decided to create a Board of Indian Commissioners, which would advise the Bureau of Indian Affairs. This Board was designed to represent all Christian denominations. Yet it soon became apparent that all of its ten members would be Protestant. And it was also apparent that all of the Indian agencies would be subject to the Board’s rule.

The resulting distribution of agencies went as might be expected from the makeup of the Board. As told by Philip Weeks in Farewell, My Nation, a standard history of the American Indian used on many college campuses, the Catholic Church “had been more active in the Indian mission field than any other denomination. The Roman Catholic Church also had contributed more than half of the funds for missions on the reservations.” Grant’s guidelines, he added, “recommended that an agency should be assigned to the missionary sect that already worked there among the Indians.” While churches other than Catholic claimed only 15,000 Indians, the Catholic Church knew it had 106,000. The Church expected to be given 38 agencies. Yet, of the 94 initial agency appointments, the Catholic Church was awarded only seven.

As a result of this unfair distribution, some 80,000 Indians, devout Catholics, were handed over to other denominations. In a number of instances, where Protestants attempted to establish parishes, Catholic Indians refused their ministry and said they were waiting for “Black Robes,” their term for Catholic priests. Catholic priests were forbidden to enter certain reservations to preach or minister to the Indians, and the Catholic Indians themselves were forbidden to attend Catholic worship even off the reservation. In one case, Chief Red Cloud of South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation wanted Black Robe missionaries on his reservation and invited one to visit. But the resident agent had the Benedictine priest escorted off the reservation at gunpoint.

It soon became apparent that one of the advantages of relying on Catholic clergy was their willingness to work in a difficult environment without substantial financial compensation, an advantage not shared by members of many other denominations. As explained by Henrietta Stockel, a former executive director of the Albuquerque Indian Center and the author of many books on Native Americans: “Problems quickly appeared. The small salary was insufficient for many agents, and in some cases rapid turnover resulted. Married men brought their wives, many of whom, despite good intentions, learned they could not tolerate the seclusion and demanded a return to ‘civilization.’

The Catholic hierarchy in the East had been urged years before to set up an office for Indian affairs in the nation’s capital. It was the unfair administration of the new Grant Peace Policy that gave the request special urgency. The spiritual interests and well-being of Catholics, both Native Americans and missionaries, thousands of miles to the west, depended in large measure on having a voice in Washington.

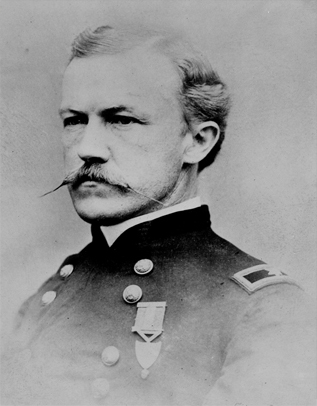

The result was the creation of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions. It brought together two people who would do more than anyone else to get this organization up and running: one, a layman, General Charles Ewing; the other, a priest and missionary, Father John Baptist A. Brouillet.

General Ewing, a veteran of the Union Army during the Civil War, was a lawyer and an influential presence in the city of Washington. His father was a senator and a cabinet secretary; both brothers were generals in the Union Army. General Ewing served with distinction in the Army of the West. He was wounded three times in the Siege of Vicksburg, but remained in the Army, rising to the rank of brigadier general. Above all, he was a man of action. In January, 1874, he was appointed the first Catholic Indian Commissioner in the United States and Western Territories by Archbishop J. Roosevelt Bayley of Baltimore.

But Ewing lacked firsthand knowledge of the needs of American Indians. That close knowledge is what Father added to the Bureau. He had been a missionary with vast experience among the Native Americans of the Northwest. Originally a professor of literature and parish priest in French Canada, he happened to meet Augustin Blanchet, the recently appointed Bishop of Walla Walla in the American Northwest. Bishop Blanchet was encouraging priests to take up work in the missions. He was impressed by the young Father Brouillet and asked him if he would consider giving up his parish to become a missionary. Brouillet responded: “Here I am.”

The two set out for Walla Walla in early 1847, a trip that took six months. As vicar general, Father Brouillet quickly helped organize the new diocese. He recruited Jesuit priests to minister to the growing population of Catholic Indians and Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur to teach in the schools. The discovery of gold enriched many in California, and Bishop Blanchet sent Father Brouillet to San Francisco to raise funds for the desperately poor Walla Walla diocese.

In 1859, fearful that homesteaders and others might challenge the ownership of mission lands, Bishop Blanchet sent Father Brouillet East on the first of several trips to Washington to protect mission property by securing clear titles, as well as to raise funds and find missionary recruits.

All of this experience made Father Brouillet the ideal candidate when, in 1874, General Ewing was looking for someone to be the first Director of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions.

The two men faced sizable challenges. As recounted by Kevin Abing of Marquette University, one was the need for finances to support the Bureau offices, as well as the many Indian missions. Their most successful source of funds was the Ladies’ Catholic Indian Missionary Association, a group created by the

Bureau to raise money. A second challenge was to secure papal approval. The existence of the Bureau was not uniformly popular within the American church. In 1879, Father Brouillet traveled to Rome to obtain the blessing of Pope Leo XIII. Six months after he arrived, he obtained a formal approval from a Vatican congregation, establishing the Bureau on a firmer foundation within the American church.

A third challenge was creating more Catholic schools in the missions. In 1873, there were only three Catholic boarding schools. Ten years later, there were eighteen. By 1890, there were 43 boarding and 17 day schools, with the federal government paying almost $400,000 a year for financing the schools. This remarkable success had unfortunate results. Other denominations, jealous of Catholic successes in this area, began to lobby for an end to the funding for all Indian schools, with the result that Congress voted in 1896 to end funding for “education in any sectarian school.” These schools then became more reliant on funding from the Bureau.

The fourth challenge was the spark that created the Bureau from the start: seeking a more equitable distribution of Catholic missions among the Indians. Here, the results were mixed.